A

few years ago the project The Deaf community

in Flanders: evaluation, sensitisation and

standardization of Flemish Sign Language

was set up. It formed part of the PBO (Programma

Beleidsgericht Onderzoek — Programme

Policy-oriented Research) of the Ministry

of the Flemish Community (98/20/129). On

the basis of the lexicographic part of this

research project a sign language dictionary

Dutch-Flemish Sign Language was created

in book form. It is about to be published

with Fevlado-Diversus.

Moreover, the project Sociolinguistic

Research of Flemish Sign Language, carried

out at Ghent

University and financed by the BOF (Bijzonder

Onderzoeksfonds — Special Research

Fund) (B/00056 — BOF/2-4/BOF2002),

made it possible to create a more elaborate,

electronic version of this dictionary. The

website you are now visiting is of high

scholarly and innovative value, but also

meets several other needs. Both projects

set out to develop a tool — being

a sign language dictionary in both book

and electronic form ? to support the education

of the lexicon of Flemish Sign Language.

This goal is now partly achieved.

The

linguistic part of the research took place

at Ghent University, in cooperation with

the Department of Germanic Languages —

CLIN (Centrum voor Linguïstiek —

Centre for Linguistics) of the Free University

of Brussels. It was conducted by supervisor

Prof. dr. M.

Van Herreweghe, English Department —

Ghent University and co-supervisor Prof.

dr. M.

Vermeerbergen, Department of Germanic

Languages CLIN, Free University of Brussels.

The

first part of the research was carried out

by Kristof

De Weerdt and Eline Vanhecke, who started

working on it in October 1999. In June 2003

Katrien

Van Mulders took Eline's place. The

development of the dictionary required the

cooperation of a Deaf native signer and

a hearing Dutch-speaking linguist, since

native speakers/users of both languages

are necessary when creating a translating

dictionary.

The

electronic version of the dictionary was

developed by Steven

Aerts and Bart

Braem, who study computer sciences at

the University of Antwerp. They were supervised

by Prof. Jan

Paredaens, Philippe

Michiels, Nele

Dexters and Jan

Adriaenssens.

Until

now Flanders had no dictionary of Flemish

Sign Language, not in book form, nor on

the internet. From various angles, however,

there was a serious need of this tool. Teachers

in the Flemish deaf schools cannot consult

any dictionary when they do not know how

to translate a certain Dutch word into Flemish

Sign Language. Nor can the teachers who

work at the sign language interpreter schools.

The dictionary is also highly needed by

various organisations (e.g. Fevlado (Federatie

van Vlaamse Dovenorganisaties — Federation

of Flemish Deaf Organisations)) that set

up sign language courses throughout Flanders

and several CVO's (Centrum voor Volwassenenonderwijs

— Centre for Adult Education). It

will in fact be interesting for all those

who come in touch with Flemish Sign Language

one way ore another.

To

be able to elicit the signs that are currently

included in the dictionary, lists of priority

terms were developed. These lists contain

the 'basic' Flemish Sign Language lexicon

and include general themes, like family,

health, colours, clothing,

occupations, etc.

The

signs were elicited from voluntary informants,

who formed regional working parties. Composing

five such regional working parties (one

in each Flemish province) was necessary,

since currently there exist five regional

sign language variants in Flanders. These

variants developed in the Flemish deaf schools

and the regions in which they are used more

or less correspond with the five Flemish

provinces: Antwerp, East-Flanders, Flemish-Brabant,

Limburg and West-Flanders. Each working

party consisted of about 6 Deaf informants,

who all met the following demands: between

20 and 50 years of age, having a thorough

command of the studied sign language variant

and using it as their first language, being

an active member of the Flemish Deaf community

and having received education in a deaf

school. Both men and women were involved

in the research.

In

each group one native signer was allowed

to look at the lists of priority terms and

was in charge of eliciting the signs by

means of eliciting material and of filming

the conversations. The informants themselves

did not get to see the Dutch words, in order

to avoid possible interference from Dutch.

The

research eventually resulted in about 90

hours of recorded language data (an average

of 1 hour and a half per session, per region).

This data was inventorised, transcribed

and analysed linguistically. The signs were

then filmed again to be able to include

them in this dictionary.

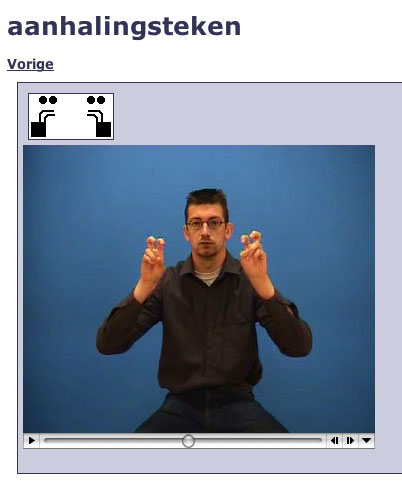

The

dictionary currently contains over 6000 signs

from Flemish Sign Language, but is still being

elaborated. The signs can be read through

SignWriting

and can be seen as moving pictures. SignWriting

is an American transcription system invented

by Valerie Sutton and the Deaf

Action Committee (DAC). It allows for

a very visual rendering of the signs, using

symbols to represent the handshapes, movements,

facial expressions, and body shifting. We

chose to render the signs in SignWriting as

well as moving pictures, because the former

can easily and effectively be used in scientific

research. It also serves various other goals:

it can be used to teach new signs in the deaf

schools, as well as for writing down texts

in VGT.

You

can search the electronic dictionary in two

directions. You can look for the VGT translation

of a Dutch word, as well as look up the Dutch

counterpart of a Flemish sign. It is also

possible to differentiate between the various

regional variants. You can look for signs

that are used solely in the West-Flemish variant,

or in both the West-Flemish and Antwerp variant,

etc... The region(s) where the sign is used,

appear(s) on the right-hand side of the screen,

next to the sign.

When

developing this dictionary we intended to

render the basic Flemish Sign Language

lexicon as accurately and completely as

possible. We did not aim at choosing the

best suitable sign for each Dutch term,

but instead wanted to include all existing

sign language variants that are currently

used in Flanders. We took into account all

lexical and regional variation that was

recorded during the collection of the data.

However,

due to the relatively small number of informants

(about 6 per province) and the fact that

we are dealing with a random indication

of Flemish Sign Language, you have to take

into account that it is simply impossible

to record all existing signs. It is possible

that you see Flemish signers use signs that

are not included here. They are by no means

worse than or inferior to the signs that

can be found in the dictionary. But you

cannot expect the informants to know all

signs used in their region or to have produced/remembered

all of them during the meetings. This is,

after all, a first basic dictionary. Further

research also remains necessary to expose

the differences between the various variants

(concerning register, age, context, gender,

...). Nevertheless, we assume this dictionary

to contain the basic Flemish Sign Language

lexicon. Moreover, thanks to this electronic

version it is possible to constantly add

newly recorded signs. The included lexicon

will therefore continuously be elaborated

and — in time — become more

complete.

In

this dictionary the Dutch word for an occupation

(e.g. carpenter, cashier, ...) is always accompanied

by the sign used to refer to that occupation.

Sometimes that sign is followed or - to a

lesser extent - preceded by the sign PERSON,

thus creating a compound sign. However, in

day-to-day conversation these signs - both

with and without PERSON - are hardly ever

used. Instead Flemish signers produce something

like 'WORKS IN A BANK' for BANKER or 'WORKS

IN A SHOP' for CASHIER. This construction

can of course not be used for every occupation

(e.g. hairdresser or baker), but it is used

quite frequently. Our informants' sign language

use was probably influenced by the situation

(presence of a camera, eliciting material,

?) when the occupation signs were elicited,

but this is impossible to avoid. To make a

difference between for example a male and

a female police officer (in Dutch AGENT and

AGENTE respectively), Flemish signers will

add MAN or WOMAN to the sign POLICE OFFICER.

This happens with a lot of occupations, e.g.

nurse (in Dutch verpleger vs. verpleegster)

doctor (in Dutch dokter vs. dokteres),

...

Dutch

— like many other languages —

has specific terms to denote the female, male

and young of a certain animal species (e.g.:

sheep ('schaap'): ram ('ram'), ewe ('ooi'),

lamb ('lam'); cattle ('rund'): bull ('stier'),

cow ('koe'), calf ('kalf')). Flemish Sign

Language also has specific signs for these

animals, but they are hardly ever used. Usually

the reference is made as follows: SHEEP +

MAN, SHEEP + WOMAN, SHEEP + SMALL.

Katrien

Van Mulders

katrien_vanmulders@yahoo.com

Universiteit

Gent

October 2004

![]()